Prehistoric Creature of the Week

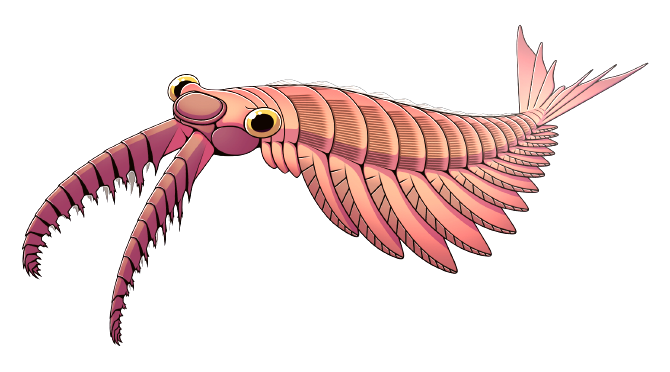

Anomalocaris: The Primordial Apex Predator

By JUNHYEOK JANG ’25

Courtesy of Jun (@ni075), image retrieved from Wikipedia

Healthy competition is immensely beneficial for one’s life. Whether your opponent is yourself or someone else, it sets a target that you ambitiously strive to overcome. In most contexts in the human world, we usually employ competition to surpass personal limitations. However, in nature, it is a dictatorial force for survival and evolution.

Throughout history, evolution has been an interspecies arms race. Prey species equip themselves with the most impenetrable defenses, while predators evolve to embody the deadliest artillery to penetrate such protective structures. As in the case of the ceratopsians against theropods, culminating in the emergence of the legendary Triceratops and Tyrannosaurus, the interspecies competition gives birth to a diversity of complex life well-suited for survival in their respective means.

Let us travel approximely half a billion years ago to the flora of the Cambrian seabed. Strange-looking creatures harmoniously swimming around suddenly scatter as a menacing shadow looms. The owner of this shadow is an animal resembling a colossal shrimp around three feet in length. Its name is Anomalocaris.

Anomalocaris was a genus of radiodontas that flourished during the early-mid Cambrian Period (520 - 499 million years ago, corresponding to Stage 3 - Guzhangian stages). Its name translates to “abnormal shrimp” in Greek. Anomalocaris was a member of the order Radiodonta, a stem group of arthropods distantly related to modern crustaceans that flourished during the Cambrian Period. Many radiodont species, including Anomalocaris and Peytoia, were likely top predators in their respective fauna on account of their size far exceeding that of others in the era, and possessed an iconic set of raptorial frontal appendages likely used for snatching prey, a conical oral structure composed of ringed tooth plates, and a multi-lensed eye enabling acute vision in all directions. Radiodonts subdivide into three families: the Tasmisiocarididae, the Anomalocarididae (of which Anomalocaris is a member), and the Hurididae. The closest Cambrian relatives of Radiodonta were the Opabiniidae and the Euarthropoda.

Reconstructions of several radiodont oral cones.

Art courtesy of Junnn11. Image retrieved from Wikipedia.

Earth’s Anno Domini

In the Gregorian Calendar, Jesus is the factor that separates Anno Domini from before the common era. In the geological time scale, an event that scientists commonly refer to as the Cambrian Explosion is what divides the Phanerozoic Eon from Precambrian times. The dominant species before the Cambrian Explosion comprised what is known as the Ediacaran biota, renowned as one of the earliest forms of complex life. Notable species include the bilaterian slug-like Kimberella and the frond-like Charnia. Then, around 540 million years ago, the world underwent a phase where interspecies competition and evolution occurred at unprecedented rates. Most of the phyla that currently exist had evolved then, replacing the Ediacaran biota that previously thrived. This period had witnessed the emergence of various iconic and legendary prehistoric species, including Opabinia, a most enigmatic arthropod with five eyes, or Hallucigenia, a spiky animal whose reconstruction remained veiled for a century. The emergence of such species has provided insights into the environmental conditions and evolutionary mechanisms of life back then.

“Throughout history, evolution has been an interspecies arms race. Prey species equip themselves with the most impenetrable defenses, while predators evolve to embody the deadliest artillery to penetrate such protective structures.”

There is little disagreement that Anomalocaris and other radiodonts have made immense contributions to accelerating evolution among the Cambrian biota. Primarily, Anomalocaris revolutionized the development of an anatomy integral and strategic for predation. Because it was a species engineered for hunting and killing; it naturally triggered immense urges for defensive evolution.

“Life is a gift that has been exclusively reserved for this planet. A major reason why it was able to thrive was due to the competition fostered by the emergence of Anomalocaris.”

Yet the ultimate weapon that Anomalocaris possessed in its formidable arsenal was not its physique: its eyes. Most scientists support one of two theories when discussing the trigger of the Cambrian explosion. Some believe that a sudden increase in dissolved oxygen enabled high rates of exergonic reactions, resulting in species being able to develop and diversify at much more complex standards. Others believe the Cambrian race for arms was also synonymous with a race for eyes - to perceive better than to be perceived. The multi-paneled eyes of Anomalocaris were transcendent even by today’s standards, enabling high-quality vision in all directions and perceiving lights far beyond our visible range. In an era where well-defined vision was scarce, Anomalocaris was a predator that could identify and pinpoint its target with its acute vision, wasting no time chasing them down and overpowering them with its gifted athleticism. To see Anomalocaris before they were seen, other animals had no choice but to cultivate their own eyes capable of ubiquitous vision, eventually prospering in their own right.

“There is little disagreement that Anomalocaris and other radiodonts have made immense contributions to accelerating evolution among the Cambrian biota.”

Despite being an apex predator of the Cambrian oceans, the oral cone of Anomalocaris lacked the strength to crush callous exoskeletons. Although previous hypotheses believed Anomalocaris to be the natural enemy of numerous trilobite species and the owner of coprolites containing their remnants, this fact has led to their rejection in modern days; many now regard that niche to have been occupied by Redlichia, a genus of predatory trilobites found in places such as Taebaek, South Korea, who likely had sufficient strength for penetrating the exoskeleton. As such, hard-shelled organisms such as Wiwaxia thrived alongside brachiopods and mollusks, in contrast to the soft-bodied prey of Anomalocaris.

The Legacy of Sight

However, as all dynasties and empires eventually do, Anomalocaris’s reign of dominance waned during the middle Cambrian. Many of its radiodont relatives perished during the Cambrian extinction, the first mass catastrophe of the Phanerozoic Eon that paved way for the upcoming Ordovician Period. The last radiodonts faded into history during the Devonian; its closest living relatives are arthropods such as shrimps and lobsters.

Even so, the legacy that Anomalocaris had left for life lives on in all of us. Thanks to Anomalocaris, we are able to see the quarterback’s pass in the air, read the passages assigned by our English and history teachers, and appreciate the scenes of this beautiful planet.

Above all, Anomalocaris was one of the greatest, if not the greatest, reasons that complex life has flourished on Earth for almost half a billion years after its demise. Life is a gift that has been exclusively reserved for this planet. A major reason why it was able to thrive was due to the competition fostered by the emergence of Anomalocaris.