Prehistoric Creature of the Week

Lystrosaurus: The Greatest Survivor

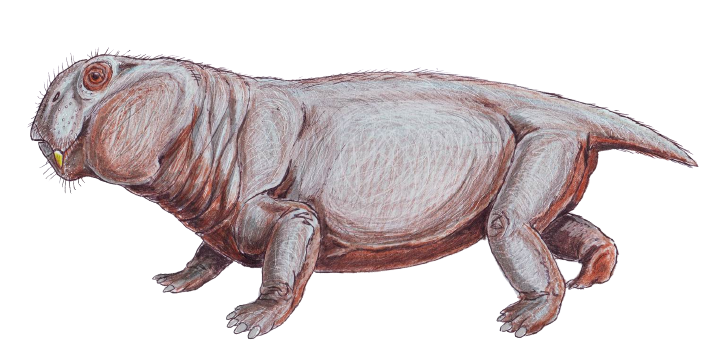

Courtesy of Dmitry Bogdaov

By JUNHYEOK JANG ’25

One of the greatest life lessons natural history offers is this: It is not the strongest who survive — it is those who survive who are the strongest.

When asked to select the most dominant species to ever walk our planet, many names will come to mind for good reasons: Tyrannosaurus, the bone-crushing tyrant king — Spinosaurus, the most deadly killer both on land and underwater — Homo sapiens, a creature whose impacts have left a mark like no other in history, and more.

The name that first comes to mind is that of a seemingly mundane animal resembling a hybrid between a pig and a lizard. It was a humble herbivore, different from apex predators such as the Giganotosaurus or tiger. Nor did it possess any impressive physical advantages such as the strength and speed of Brachiosaurus and Velociraptor, respectively.

However, this animal was rivaled by none other in its adaptability and consequently dominated a world decimated by the deadliest catastrophe in history. Distinctively, it constituted 95 percent of all terrestrial life during its era, a record that remains to this day and is unlikely to be ever broken. This legend is a creature often underappreciated, yet has left an immense impact on the field of natural history and also deserves recognition as an epitome of finding true success in one’s life. Its name was Lystrosaurus.

Biography

Lystrosaurus was a genus of dicynodonts, a clade of sturdy herbivores with a dual set of tusks, that lived during the middle Permian through the early Triassic (273 - 237 million years ago, estimates based on Roadian - Ladinian eras). Its name translates to “shovel lizard” in Greek. Lystrosaurus’ palates and mandible structures possessed a dense beak likely used for underground digging and uprooting vegetation. Large species of Lystrosaurus, such as L. maccaigi, had lengths up to three meters, while average species, including L. murrayi, were measured to be around one meter. Lystrosaurus fossils have been found in India, Africa, and Antarctica, serving as evidence for continental drift.

The Permian Extinction

The Permian was a period in which many significant reptile lineages, including a mammal-like group known as synapsids, flourished. A representative synapsid was Dimetrodon, the apex predator that terrorized the Cisuralian epoch (early-mid Per mian). Many regard it as the most prominent organism of the Permian and as one of the greatest in history. Synapsids differentiate into two orders: pelycosaurs and therapsids. Therapsids, including Lystrosaurus, gradually replaced the pelycosaurs (which Dimetrodon was part of) as the Cirusalian epoch transitioned into the Guadalupian.

The Permian is also the period in which smaller continents congregated into the supercontinent Pangea. These continental drifts triggered a cascade of climate change which, by the end of the Permian, resulted in global warming at such a rapid rate that all life forms were jeopardized. The decisive blow that triggered the PermianTriassic extinction, conventionally referred to as the Great Dying, was a series of volcanic activity in the Siberian Igneous Province. An immense quantity of carbon dioxide led to elevations in global temperatures and widespread anoxification and acidification in oceans. This catastrophe concluded with the obliteration of 96 percent of life, including Trilobita, which were present since the Cambrian period and had survived numerous mass extinction events; only the remaining five percent, including the Lystrosaurus, survived into the Triassic period and the Mesozoic era.

The Greatest Survivor

Before the PermianTriassic extinction, Lystrosaurus was a common prey species like deer in the present era. As aforementioned, in the early Triassic following the calamity, Lystrosaurus accounted for 95 percent of all terrestrial vertebrae of its time, a record that still stands. How could a docile, seemingly mundane creature possibly end up as the ultimate survivor and the most dominant of all time?

Lystrosaurus possessed numerous features advantageous for survival on a scorched Earth. Abrasions found in the beaks of numerous specimens suggest that Lystrosaurus spent a significant part of its life underground, finding sanctuary from the perils of the outside world. Modern analyses also speculate that Lystrosaurus had relatively large lungs, allowing for sufficient oxygen intake amidst a limited supply. However, considering that close relatives such as Diictodon and Eodicynodon also possessed similar qualities yet did not survive beyond the Great Dying, other factors must have contributed to Lystrosaurus’s unprecedented viability.

Lystrosaurus was also adept in long-distance travel, allowing it to disperse across Pangea and escape to the relatively less affected southern regions. Although quite distant today, Antarctica, Africa, and India composed the area that would eventually diverge into the continent Gondwana; the discovery of Lystrosaurus fossils in such regions, as shown below, corroborates the existence of Pangea.

Of course, a certain degree of luck played a part in Lystrosaurus’s immense survival. Lystrosaurus had the fortune of living in a world bereft of significant predators. Dimetrodon, a devastating predator to many contemporaneous tetrapod herbivores, was in its twilight days of dominance when Lystrosaurus emerged. Many carnivorous therapsids posing viable threats to Lystrosaurus perished during the Great Dying. Mainstream Triassic predators such as Postosuchus or Nothosaurus either rose to prominence years after Lystrosaurus’s decline or lived in different ecosystems.

Regardless of the cause, no other single genus has dominated the planet as Lystrosaurus has; Lystrosaurus deserves recognition as the greatest survivor in history.

An Underappreciated Legacy

Sadly, Lystrosaurus faded into history during the Triassic period. As biodiversity of animal and plant life recovered from the Permian-Triassic extinction, large predators and competitors, including some of the first dinosaurs, emerged, causing Lystrosaurus to dwindle in number and slowly evolve into other species. Lystrosaurus and its lineage of therapsids ultimately perished during the Triassic-Jurassic mass extinction. Because its niche was often on the lower end of the food pyramid and the species went extinct long before the Golden Era of the Jurassic and the Cretaceous, Lystrosaurus is often mistakenly seen as merely one of many prey organisms that have passed through time.

In reality, Lystrosaurus played a significant part in the renaissance of life from the ashes of the Permian-Triassic extinction and provided immense assistance in revolutionizing the way modern researchers understand the continental drift of Pangea. For such reasons, it is only natural that Lystrosaurus deserves nothing less than to be remembered as one of our planet’s greatest legends. Lystrosaurus’s unparalleled viability has allowed for biodiversity to be sustained at high levels as life began to recover from the cataclysmic aftermaths of the Great Dying. Without Lystrosaurus, well-known species such as Tyrannosaurus and Spinosaurus and even Homo sapiens may have never existed.

Most importantly, Lystrosaurus is an excellent mentor for us to reflect on what success really means. In life, many people outperform us in many ways; there is always someone who surpasses us in intelligence, athleticism, or the ability to make social connections and garner popularity. However, Lystrosaurus teaches us that, in the end, those who survive until the very last, using every resource to its fullest, are the true winners. One’s evaluation as an individual ultimately comes at the end of one’s life, when one has lived through it all.

Lystrosaurus was not a deadly predator like Tyrannosaurus, did not possess a versatile offensive prowess on land and underwater like Spinosaurus — nor did they single-handedly impact the planet so extensively like Homo sapiens. Yet no other species has surpassed Lystrosaurus in surviving and dominating Earth, especially throughout a time when life on Earth was meeting its greatest challenge yet.

Courtesy of The Geological Society